It has been some time since I last posted anything, mainly due to holidays but also because I wanted to gather as much information as possible about this topic.

As with most towns Pickering used to have a workhouse and although there is no evidence of it left today I thought it would be interesting to look into the history. Unfortunately, I have not been able to discover as much as I would have liked but I thought it best to put pen to paper, as it were, and publish something.

Pickering had a workhouse of sorts in the late eighteenth century. Its location is usually given as Undercliff. This area of town still remains and is mostly a row of cottages tucked under the cliff below the castle and opposite the train line heading north to Whitby. I’ve tried searching old maps for clues as to where the workhouse was but I’ve been unsuccessful. I am assuming it may have stood on land to the west of the road which is now occupied by the train station and its associated yards, lines etc. Undercliffe now refers to the stretch of road from the junction of Park Street and Castle Road stretching north out of the town. However, names do change. I have discovered that what we now know as Park Street (no idea why it is called this) was once Bakehouse Lane. Little is known of the inhabitants of this workhouse (or poorhouse) but it was probably quite small.

A Poor Law Union was established in Pickering at the beginning of the reign of Queen Victoria and a new building was erected to the north-east of the town on Whitby Road. It was officially opened in 1838 and if we look at the census of 1841 we find that Richard (from Pickering) and Ann Spaven were the master and matron of the workhouse and they had an assistant called Elizabeth Lyth. They appeared to have just forty-four residents at that time ranging from infants to a man of 90 years of age. The Spavens remained there for some time but by 1861 George (from Marton) and Sarah Ward had taken their place. There are now only twenty-four ‘inmates’ listed on the census, age range four months to 79 years.

Moving on a further twenty years and Francis (from Birdsall) and Mary Maul are in charge of fifty-two inmates with ages ranging from five months to 83 years. Just ten years later and Robert (from Pickering) and Mary Simpson are ensconced there. Sixty-nine inmates reside there too (one month to 87 years). Our final peek at the census, in 1911, shows Burton (from Osmotherley) and Mary Holmes in charge of sixty-eight inmates with ages ranging from three months to 93 years.

The majority of the inmates throughout this period are from Pickering and its immediate area though there are some from as far away as Scotland. Many of the surnames are familiar and no doubt it is their descendants that still live in the town.

Whilst the workhouses were meant for those that could not afford to support themselves financially it appears they were often used as a convenient place to keep people for a variety of reasons. Most workhouses had an infirmary wing, Pickering included, and these were sometimes used by local doctors in place of a hospital (which would have been few and far between and expensive). A report in the Whitby Gazette on Saturday, 25th December 1886, gives an example of the workhouse being used in place of a hospital.

Singular Affair.

A man named John Charles, a labourer, of Thornton, is now lying at the Pickering Workhouse in a serious condition, brought about by peculiar and suspicious circumstances. The poor fellow, it seems, was suffering from an infectious skin disease, and he applied to a local chemist and druggist, who sold him box of ointment. The application not proving efficacious, Charles says he went again and was supplied with some medicine. He, however, became so much worse that Dr. Robertson, of Thornton was called in, and recommended the sufferer’s immediate removal to the Pickering Workhouse. Since his reception there his condition has become so serious that his deposition was taken before Major Scoby, and Captain Mitchelson—the Guardians, the Superintendent of Police, and the chemist’s assistant being also present, and the latter cross-examined the expected dying man. Charles was in an extraordinary condition at the time, his skin having peeled off his body, some portions of which were enormously swollen.

A further article in Shields Daily Gazette reports that Mr Charles died on 11th January 1887. The attending doctors told the coroner that they were unaware of any drug or combination of drugs that could cause this effect so he returned a verdict of death by natural causes.

The other use of the workhouse was in place of a prison or place of detention. Another newspaper article, York Herald, Wednesday, 10th February 1892, tells a tale of a young man.

An Incorrigible Pickering Youth Liberated.

The Pickering police have recently had some trouble with a lad named Bointon, aged 11 years, who, after being charged with stealing certain moneys from the shop of a local confectioner, was remanded to the Pickering Workhouse, and while there he proved incorrigible and succeeded in effecting his escape. After recapture he was lodged in the custody of the police. On being brought up on remand the magistrates ordered Bointon’s removal to the York Industrial School for a period of three years. Strange to say, however, before the expiration of a week the lad has been brought back to Pickering with the message that he was incurable, and so James, instead of receiving the punishment ordered by the justices, is once more enjoying the company of his old comrades.

It seems the workhouse could be used for anything the community required.

In the 1930s the workhouse finally closed and became a children’s home.

There were several advertisements for workers in the children’s home, one appeared in the Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer on Friday 22nd March 1935 and ran as below:

CHILDREN’S HOME. PICKERING.

Applications are invited for the following appointments

(a) SUPERINTENDENT and MATRON.

(b) MATRON.

(c) BOYS’ ATTENDANT (resident or nonresident).

The Committee require two officers for duty at the Pickering Children’s Home, but have not yet determined whether the Male Officer shall be the Superintendent or the Boys’ Attendant. They therefore invite applications from married couples for the positions of (a) Superintendent and Matron. They also invite applications from single persons for the posts of (b) Matron and (c) Boys’ Attendant. It is not yet decided whether the latter officer shall live on the premises.

The salaries attached to the appointments are:

SUPERINTENDENT and MATRON Up to £250 per annum for the Joint appointment, according to qualifications

MATRON Up £125 per annum, according to qualifications

BOYS’ ATTENDANT (resident): £60-£80 per annum.

BOYS’ ATTENDANT (non-resident): £125 per annum.

The resident officers will be allowed board and lodging, and all are superannuable.

Applications, in applicants’ own handwriting, stating age, present and previous occupation and experience, and when able to commence duty, accompanied by copies of not more than three recent testimonials, must be sent to the undersigned not later than 30th March, 1935. Previous Poor Law experience not essential. Application forms are not provided. Applicants will be required to undergo such medical examination as the County Council may direct. HUBERT G. THORNLEY. Clerk of the County Council, County Hall, Northallerton. 6th March.

In the 1939 register the matron is listed as Blanche Parnaby with her assistant Kathleen Broadbent and two childrens’ attendants, Margaret McLoughlan and Dora Teasdale. Due to the privacy laws relating to this register it is impossible to tell how many children were living there at the time.

Later still the workhouse was demolished and in its place there is now an older people’s home.

It is difficult to imagine what it was like living in an institution in those times but we can be assured it was generally grim. If you want to visit a workhouse museum to perhaps get a better idea of life there I can recommend two that I have visited.

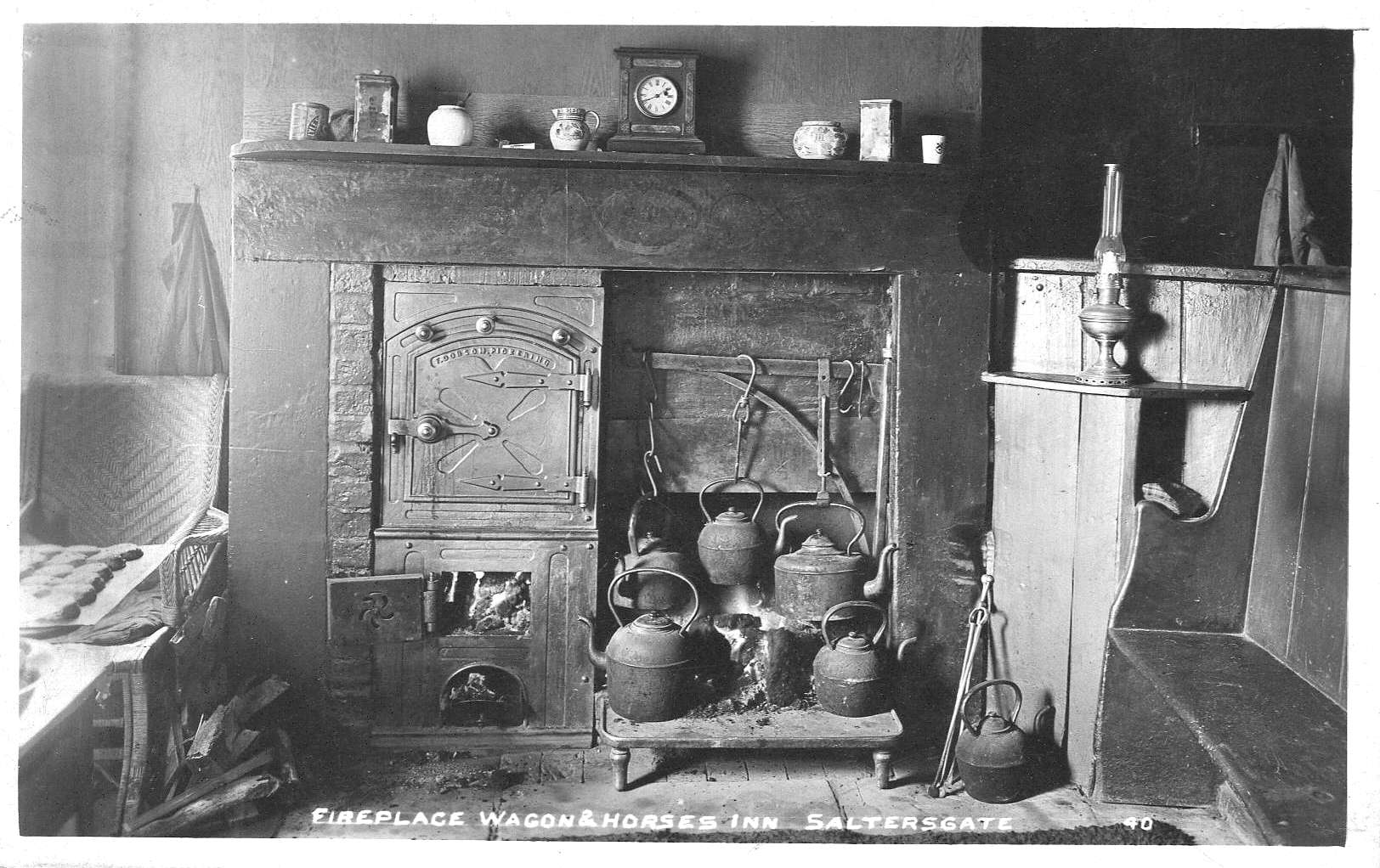

A recent trip to Robin Hoods Bay meant me travelling north from Pickering along the Whitby road. About halfway between Pickering and Sleights the road circles the Hole of Horcum before dipping down Saltergate bank, around the Devil’s Elbow, and heading on past RAF Fylingdales. At the bottom of the bank stands a building now known as the Saltersgate Inn, a place I have drank in a number of times and which has several stories attached to it. Unfortunately, on this trip, it was evident that the building was derelict.

A recent trip to Robin Hoods Bay meant me travelling north from Pickering along the Whitby road. About halfway between Pickering and Sleights the road circles the Hole of Horcum before dipping down Saltergate bank, around the Devil’s Elbow, and heading on past RAF Fylingdales. At the bottom of the bank stands a building now known as the Saltersgate Inn, a place I have drank in a number of times and which has several stories attached to it. Unfortunately, on this trip, it was evident that the building was derelict.